—Using Color Pencils In-Depth While Using Primary Colors & Baby Oil

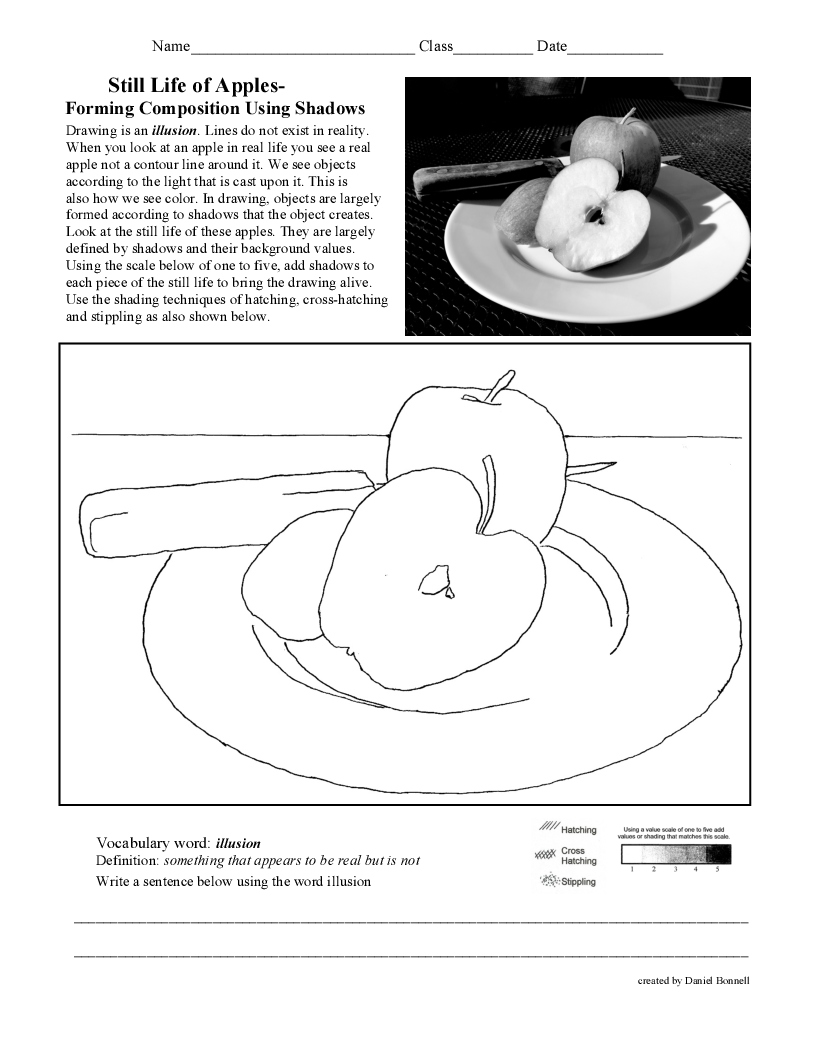

—Seeing Shadows as Defining Composition

This week you have four drawings to produce. Please drag the specific work sheets to your desktop and follow the instructions. You are discovering how primary colors gain depth through neutral colors being applied last. Starting with blue as a base, then red and then yellow you can create dynamic color and then your tones and values come last with adding black or white (hue or tint). Below this lesson you will then discover The AshCan School of Art lesson. The artists of that period used vivid color as well in their art. They were masters of the neutral colors to embellish city scenes in New York.

You have one week to complete both of these assignments. Please make a photos of you work (2 up) and send them to ihs.db@yahoo.com

“Do whatever you do intensely. The artist is the man who leaves the crowd and goes pioneering. With him there is an idea which is his life. ”

Artists of the Ashcan School

Discovering the Ashcan School and Genre Painting

At the turn of the last century, a group of young artists appeared who were set on challenging the refinement, polish, and idealistic American Impressionists who then dominated the art scene. Philadelphia's Robert Henri was the leader of the group which was made up of John Sloan, Everett Shinn, George Luks, and William Glackens. Each one varied in style and subject matter; yet, all were urban realists who adhered to Henri's motto "art for life's sake," rather than "art for art's sake." Despite their common economic and ethnic backgrounds, each approached the urban scene in a unique manner. Henri had studied at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Art, as well as at Paris's Academie Julian. He began to mentor the four artists, all of whom were newspaper illustrators, circa 1892; we consider this grouping to be the first generation of Ashcan School painters. The second generation commenced with Henri's move to Manhattan and the inclusion of his New York student George Bellows.

The Eight is Formed

In 1908, the core Ashcan School artists were joined by three other painters, Edwin Lawson, Maurice Prendergast, and Arthur B. Davies, to form The Eight. This new formation only exhibited as a group once, at the MacBeth Galleries in New York. What united this varied grouping of artistic rebels was their opposition to the conservative and very powerful National Academy of Design's system of juried exhibitions. Henri and many other artists believed that the National Academy was not supportive of more liberal, modern ideas and was indifferent to their art. Opposing competitions and the selections of conservative juries, Henri advocated a no-jury, no-prize, open policy for exhibitions that he felt nurtured a creative atmosphere. The Eight was putting power back into the hands of the artists who selected the works, and its members designed the installation themselves.

Snow in New York by Robert Henri

Robert Henri's Snow in New York (1902, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC) is a wonderful example of the Ashcan School. He depicts New York's brownstone apartments hemmed in by faceless city blocks. The noise of the city is quietened by the newly fallen snow, which reveals grey slush and traffic ruts left by the horse and carts. The artist urged his students to reject the 'Ideal' and instead to focus on 'Reality'. This was the core of his individual contribution to American art. He promoted the idea that painting should spring from life, not from academic theories or classical aesthetics, and became a powerful influence in persuading young painters to capture the richness of urban reality, rather than rely on academic notions about art.

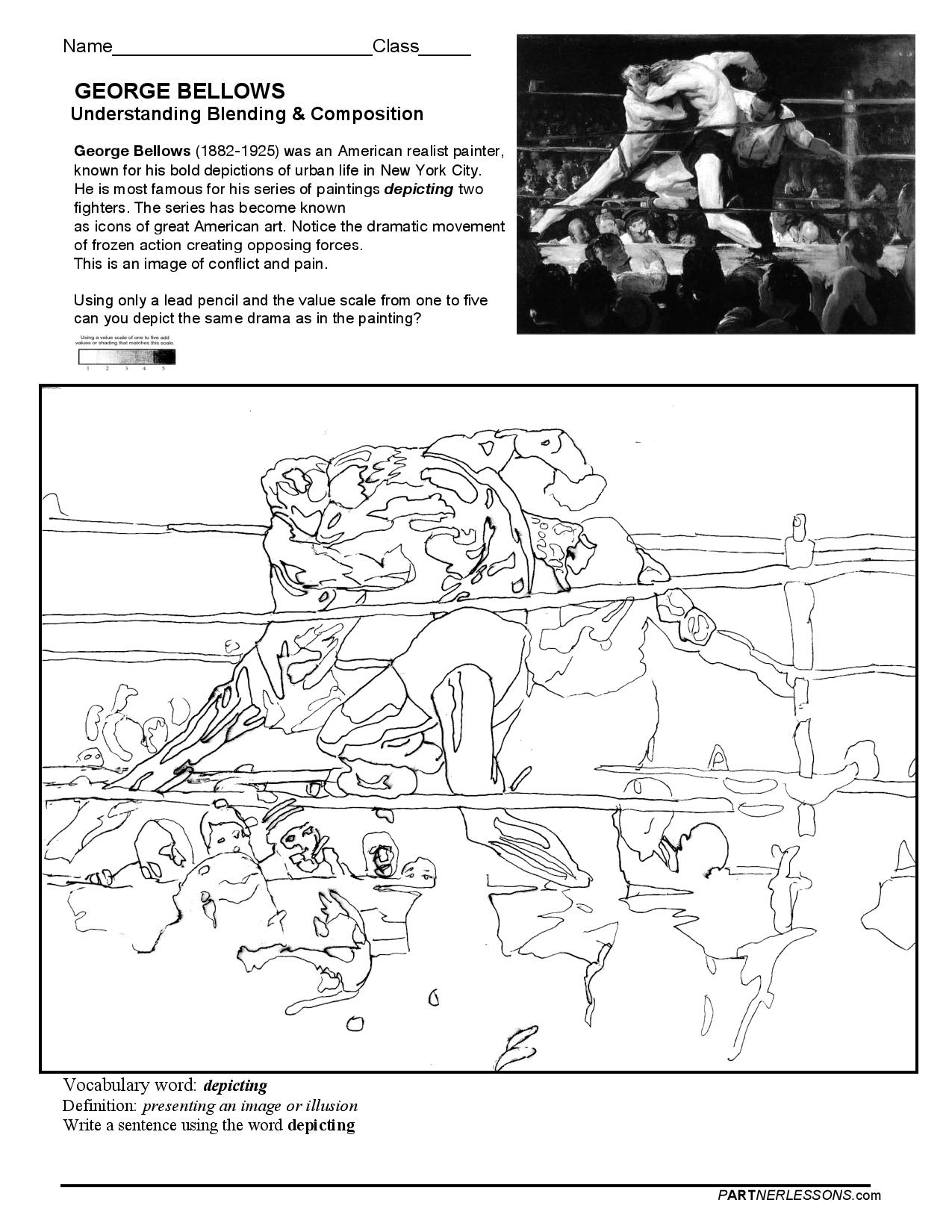

The Stag at Sharkeys by George Bellows

The Stag at Starkeys is one of Bellows most famous works. Bellows was no stranger to Sharkey’s Athletic Club, a raucous saloon with a backroom boxing ring, located near his studio. Founded by Tom “Sailor” Sharkey, an ex-fighter who had also served in the US Navy, the club attracted men seeking to watch or participate in matches. Because public boxing was illegal in New York at the time, a private event had to be arranged in order for a bout to take place. Participation was usually limited to members of a particular club, but whenever an outsider competed, he was given temporary membership and known as a “stag.” Although boxing had its share of detractors who considered it uncouth at best or barbaric at worst, its proponents—among them President Theodore Roosevelt—regarded it a healthy manifestation of manliness. Around the time Bellows painted Stag at Sharkey’s, boxing was moving from a predominantly working-class enterprise to one with greater genteel appeal. For some contemporaries, boxing was a powerful analogy for the notion that only the strongest and fittest would flourish in modern society.

Forty Two Kids by George Bellows

Forty-two boys or "kids" swim in the dirty waters of New York City's East River to escape the stifling heat of ill-ventilated tenement apartments. Under the dark cover of night at the city's edge, the boys use a modified dog paddle as their stroke to push floating garbage out of their way. George Bellows's brushy, rough application of oil paint marked the boys' social class onto their bodies, which are nude and scrawny. The term "kid" was popularized by the cartoon Hogan's Alley, whose protagonist was "The Yellow Kid," a slum-dwelling hooligan.

Bellows's depiction of city boys diving off splintered piers and reveling in their freedom, coupled with his bravura, painterly style appalled several New York art critics. One caustically appraised Bellows's canvas, asserting that "most of the boys look more like maggots than humans." While many similarly derisive words denigrated poor immigrants, the boys themselves are clearly enjoying their escape from society's scrutiny. Bellows's work typifies the Ashcan School artists' interest in everyday subject matter, the urban poor, and the overall vitality of life.

The hair Dresser by John Sloan

John Sloan was another renown Ashcan School artist that embodied the movement with his work. One popular painting of his is The Hair Dresser shown above. For both the viewer and the figures in this street scene, the focal point of Sloan's painting is a female hairdresser, visible through the second story window of a building. Positioned in side profile, with gloved hands she is coloring the long red hair of a woman whose back is turned to us. It is a slice of everyday life, complete with the overwhelming visual display that characterized the urban experience in the early 20th century.

This work is an important early example of the Ashcan School, a group in which Sloan played a key role. Artists associated with this style featured day-to-day moments of life in New York City, preserving their mundane but gritty realism. At the same time, the painting becomes a statement about looking - both at the painting itself and at the world. According to John Loughery, "the theme of the window frame and the very act of looking inevitably became almost a preoccupation for Sloan...."

Sloan spent hours walking the city streets and sketching scenes like the one found here. He also worked from his window and rooftop, watching people go about their lives. At the same time that he documented this urban community, he often captured loneliness, the lack of connection, and the sense of isolation that can exist among a crowd. The private act of grooming is performed for an audience (unknown to the client), but all of these people remain strangers to each other. It is an accidental community, bound together for a fleeting instant.

Using watercolors, recreate the painting The Stag at Starkeys below.